Highlights 2020: Week 20

Labor as leverage, plus where wealth comes from.

Fortunes require leverage. Business leverage comes from capital, people, and products with no marginal cost of replication (code and media).

[…] Labor means people working for you. It's the oldest and most fought-over form of leverage. Labor leverage will impress your parents, but don’t waste your life chasing it.Naval, “How To Get Rich, Without Being Lucky”

When most Millennial entrepreneurs talk about leverage, generally, they mean capital, code or media. Labor is the red-headed stepchild of leverage.

For good reason. It’s a pain-in-the-neck to scale.

I’d posit, it’s hardest but it’s also the most robust.

Consider SOPs. McDonald’s seems to have top-notch systems. But anyone who has ever run a business would agree, those systems aren’t static. They’re fragile. The supplier changes hamburger size and the SOP has got to change too.

The SOP is scalable instantly quick. A human who can be taught to understand process scales slow, but is robust.

The ultimate cause of wealth is not land or resources or labor but the human mind

James V. Schall, S.J., On Christians and Prosperity

[…] how vast is the role of technology, that ally of work that human thought has produced, in the interaction between the subject and object of work (in the widest sense of the word). Understood in this case not as a capacity or aptitude for work, but rather as a whole set of instruments which man uses in his work, technology is undoubtedly man's ally. It facilitates his work, perfects, accelerates and augments it. It leads to an increase in the quantity of things produced by work, and in many cases improves their quality.

John Paul II, Laborem Exercens (emphasis added)

Algorithmic traders fascinate me. It’s a problem I’d put firmly in the “too hard pile”, but seems to have lots of lessons that can be ported over to other disciplines.

Let’s start with this obvious statement: traders that write code to trade seem to do well (comparing Bridgewater to Renaissance seems to back this up - but I’m just going off what I’ve heard smart people say, there).

But the problem is, as they uncover an edge, it’s swiftly eroded.

The tenure of a successful trader seems significantly longer than a successful algorithm.

People are the classic chaotic system. We’re messy. We have good days and bad days. We get bored and don’t want to work. We get excited and want to chase shiny objects. We get married and have priorities shift. We make secret decisions, that we don’t even let ourselves in on, like why we’ll buy or marry or move.

A blog post is predictable. You access the Google Doc, you get the text. A piece of software is [mostly] predictable. You input commands it outputs the result. Capital is predictable. A dollar is a dollar.

People are not. We are all over the map.

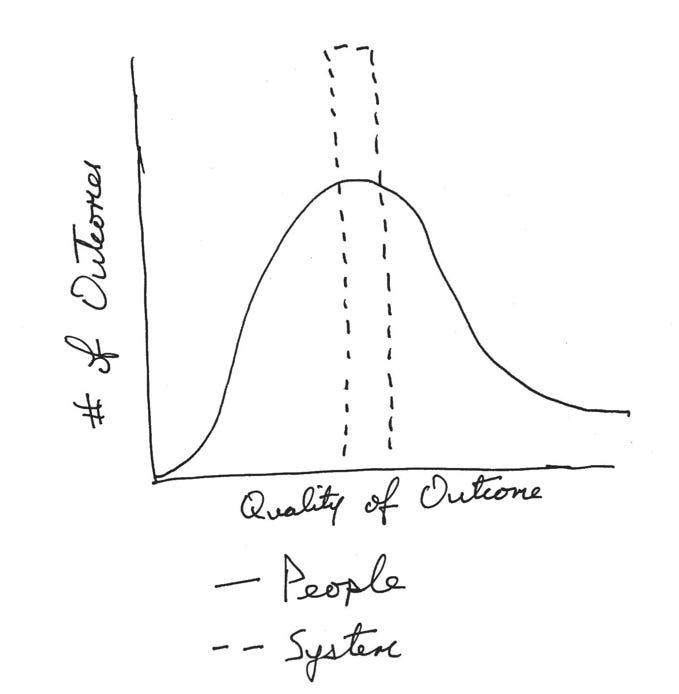

Here’s a model of predictions around a process vs person outcome:

I should’ve drawn this curve with the quality of system outcome more to the right. But an important detail is, if you add up all the outcomes under the people curve, it’s got to be greater than the system curve, if for the mere reason that people created the systems, so are always going to be a step ahead.

The key takeaway is, you know more or less what you’re going to get with the system. If the inputs are consistent, the outputs are consistent.

People on the other hand, vary. Most people do mediocre, but respectable work. A few create massive Ponzi schemes and destroy billions of dollars in wealth. A few invent cars, compose symphonies and save humanity.